I realize nobody wrote it down until 300 years later. And, well, my own diaries and sermons were burned during the persecution under Diocletian. But I’d like to set the record straight, after so many centuries of distortion and exaggeration.

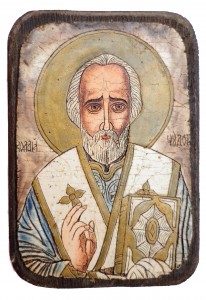

My name is Nicholas, Nicholas of Myra. And this is my story.

I was born in 280 A.D. in Patara. It was a town of some consequence then, or at least we liked to think so. Patara was a trading center in Asia Minor and my parents, Theophanes and Nonna, were wealthy merchants.

They were quite old when I was born. Maybe not as old as Sarah and Abraham in the Bible, but I know my mom did pray for a child a long time. They thought I was a gift. Frankly, they were gracious people who saw everything as a gift.

My parents held their wealth lightly, as lightly as a feather blowing down the stone streets, under the aqueduct and out into the wooded hills. I always knew that everything we had was never really ours.

One of the monks would later write that my parents were “of substantial lineage, holding property enough without superfluity.” I guess it felt like superfluity at the time. We certainly lacked nothing.

I had a Greek tutor, for example. He was a bodyguard, actually. I loved to hang out down near the shipyards and listen to the sea men talk about their adventures in Rhoads, Cyprus, Antioch, Alexandria, even Rome. It was more exciting than the market, what with all its beads and glass and fabric and dead cows and such.

It was no place for a boy, my mom used to say, especially after I repeated a few words she didn’t think I should know. But dad just told the tutor to keep me out of trouble, more for mom’s benefit than mine. There is a lot to learn, dad said. We both knew trouble is where you learn most of it.

Learning occupied most of my day, actually. And I’m not just talking about school. I was an early reader and a good student and fortunate to have access to scrolls and such. But we also took church very seriously.

In fact, the Apostle Paul had visited our city years before and we read his letters to the other churches regularly, poring over them and memorizing them. And the gospels especially. Jesus seemed so fresh and real to me, even when I was a kid. Mom even joked that when I was a baby I wouldn’t even nurse on fast days, but I joked back that it was just because she wouldn’t feed me. I was named after her brother, Nicholas, who was our bishop. The name means “the people’s hero,” which took more than a little getting used to.

Even then there was talk of my becoming a pastor. “I see a new sun rising and manifesting in himself a gracious consolation for the afflicted,” my uncle said. I never saw myself as a “new sun,” that’s for sure. But I did have a tender heart. I loved to go with mom when she went out “distributing to the necessity of the saints,” as she called it. It was often just a loaf of bread left on someone’s doorstep.

In those days the Christians in our city often met in homes, eating together and encouraging each other. My favorite place to meet was at Stephen’s house. He and Anna were good friends of my mom and dad, members of the merchant’s guild and the city council.

I’m not saying I liked to go there because of his three beautiful daughters. I was just a kid after all, if not a precocious one. I just liked that all of them made every one feel welcome, even the many slaves who followed Christ—“not as a slave, but as a beloved brother,” as Paul wrote to Philemon

This didn’t sit well with every one. Many people were suspicious of us, especially the Romans. The Romans were suspicious of everyone. The empire was in decline and insecurity makes men do stupid things. Even evil things. It was very sobering when we heard that Polycarp had been burned at the stake. And of course we all knew about Nero, who blamed the great fire in Rome on Christians.

But we were a brave and cheerful lot. My uncle Nicholas insisted that a life in service to Christ was a life of sacrifice and joy. My childhood was a lot more of the latter. We were both blessed and grateful.

That was until the winter the plague spread throughout our entire province, cutting down entire families. Ships would not come into the harbor. Caravans would not enter the city. The money-lenders were cruel and the famine was relentless. Sometimes I prayed all night for the people in our city. I was 13.

And then one weekend both my parents died. Mercifully their passing was short. My grief was not. I missed mom’s laughter, reverberating down the halls. And I missed dad’s wisdom. He always knew what to do. And I didn’t.

I still answered the door and tried to help the people asking for help. That’s what they would have done. But when the door closed, the stone walls seemed harder and colder. Like my heart.

But it wasn’t time that healed my grief. I moved in with my uncle and became more involved in his work. I spent a lot of time with the orphans. I knew what they were feeling. And I was learning that being busy was better than feeling sorry for your self. Everywhere we turned there were sorrows enough.

Stephen even lost his fortune when two ships he had staked never returned. He had already lost Anna in the plague. As his debtors crowded in, threatening even to take his daughters, I knew what I had to do. My parents left me a lot of money. Since I was planning to continue my studies and enter the ministry, it wasn’t going to do me much good. Neither were the girls, for that matter.

So, well, I gave them gold for their dowries. Three bags, actually. One for each daughter. I tried really hard to do it in secret, dropping them through the window at night. I don’t know anything about the one bag falling in a shoe or stocking or anything like that. It doesn’t matter, really.

I just know that Stephen caught me one night, as I tried to sneak down the street behind their house. He was so grateful it was embarrassing. The chronicles got that mostly right. He said: “If the Lord great in mercy had not raised me up through thy generosity, then I, an unfortunate father, already long ago would be lost together with my daughters in the fire of Sodom.”

Or he said something very like it. Stephen always had a flair for the dramatic. I’m just glad he got the “Lord great in mercy” part it there. It explains a lot, as we will see.

I asked him not to tell anyone, but of course he did. I had been giving away a lot of money, actually. There were so many needs. People started to put two and two together and come up with ten or something, giving me a lot more credit than I deserved.

Bankers and pawn-brokers even three gold balls as a symbol of their willingness to help people in need.

But let’s be serious.